Allergan Ruling Reinforces Value of Patent Term Adjustments

Editor's note: Authored by Betsy Flanagan, Sam Matthews and Matthew Pavao, this article was originally published in Law360.

On Aug. 13, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held in Allergan USA Inc. v. MSN Laboratories Private Ltd.[1] that "a first-filed, first-issued, later-expiring claim" cannot be invalidated for obviousness-type double patenting, or ODP, "by a later-filed, later-issued, earlier-expiring reference claim having a common priority date."

This decision clarifies the scope and applicability of the court's 2023 In re: Cellect decision,[2] which held that a patent benefitting from patent term adjustment, or PTA, under Title 35 of the U.S. Code, Section 154(b), can be invalidated for ODP over earlier-expiring patents in the same family.

The court's decision is a positive outcome for patentees, ensuring that PTA awards for first-filed, first-issued patents cannot be stripped away by later-issuing child patents that expire earlier.

In this Hatch-Waxman case, Allergan sued several generic manufacturers seeking approval to sell copycat tablets of Allergan's Viberzi, or eluxadoline, tablets. Allergan asserted the first patent applied for and issued on eluxadoline, the active ingredient in Viberzi, or U.S. Patent No. 7,741,356, referred to below as the '356 patent.

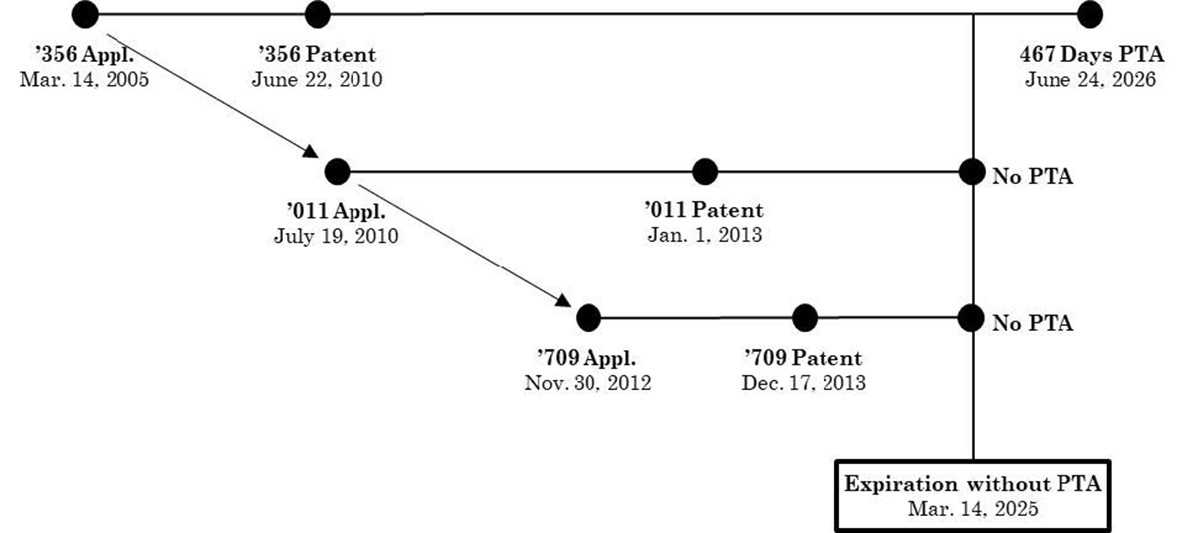

The '356 patent claimed a genus of eight compounds, including eluxadoline. The '356 patent expires on June 24, 2026, including 467 days of PTA awarded by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Background

The generics argued that the '356 patent was invalid for ODP based on later-filed, later-issued child reference patents that expired earlier because they were not awarded any PTA, referred to below as the '011 patent and the '709 patent.

The child patents have narrower claims than the '356 patent covering eluxadoline itself. The below diagram from the Federal Circuit[3] illustrates the relationship between the '356 patent and the child reference patents.

The generics argued — and Allergan conceded — that the claims of the '356 patent, to a genus including eluxadoline, were not patentably distinct from the claims of the child reference patents, to eluxadoline itself. However, Allergan argued that the later-filed, later-issued child reference patents could not be ODP references to the '356 patent.

The U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware considered itself bound by the Federal Circuit's holding in Cellect. There, the Federal Circuit held that, "ODP for a patent that has received PTA, regardless of whether or not a terminal disclaimer is required or has been filed, must be based on the expiration date of the patent after PTA has been added."[4]

The district court thus held that the child patents were proper ODP references, and that the claims of the '356 patent were invalid for ODP because it was not patentably distinct from child patent claims.

The Federal Circuit Decision

The Federal Circuit reversed, holding that, although Cellect established a rule that courts must assess ODP based on expiration dates after PTA has been added, it "does not follow ... that the [challenged patent] must be invalidated by the [child reference patents] simply because it expires later."[5]

Rather, because both of the child reference patents were filed after, issued after and claimed priority to the challenged patent, neither could serve as an ODP reference to the challenged patent. This case establishes that the first-filed, first-issued patent in a family "sets the maximum period of exclusivity for the claimed subject matter and any patentably indistinct variants."[6]

Central to the court's reasoning was the underlying purpose of the ODP doctrine: "to prevent patentees from obtaining a second patent on a patentably indistinct invention to effectively extend the life of a first patent to that subject matter."[7]

Here, the '356 patent was not a second patent, but in fact was the first patent in the patent family — whether judged based on filing or issue date — and it could not be invalidated over the later-filed, later-issued child patents.

Takeaways

This decision creates an asymmetry in ODP practice, where a parent patent may be insulated from an ODP challenge over later-filed, later-expiring child patents but can be used as an ODP reference for challenging those child patents.

Now, more than ever, patentees and practitioners should carefully consider the order in which various subject matter is pursued in a series of patent applications in the same family.

The first-filed, first-issued patent in a family often receives the most PTA and may now often be the patent least vulnerable to an ODP challenge. It often may be desirable to pursue the most critical subject matter — e.g., for a pharmaceutical patent application, species-level claims to a clinical product — in this first patent.

The Allergan decision also affirms the significant value of PTA. It is critical for practitioners to consider the potential impact of any action that might reduce the amount of PTA awarded, such as taking an extension of time, delayed filing of an information disclosure statement or filing a terminal disclaimer.

After Allergan, this is particularly true for the first-issued patent in a family, as it also may affect the exclusivity period of later-filed, later-issued patents claiming patentably indistinct variants.

This case also will affect the interplay between PTA and patent term extension, or PTE, under Section 154. When seeking to protect subject matter that may be eligible for PTE, it becomes even more important to adopt a familywide strategy at the outset of prosecution.

Selecting a patent to request PTE requires careful balancing of many factors (including the existing expiration date and including PTA, if applicable), the enforceability of the claims, and the likelihood that the patent will survive an invalidity challenge during litigation.

Early strategic planning is key to maximizing a patentee's exclusivity — via PTA, PTE or both — for their most important subject matter.

When analyzing a patent portfolio, it is often necessary to assess the risk of a double patenting challenge to the patents in the portfolio. The new ODP asymmetry introduced by Allergan means that practitioners should pay close attention to the filing and issue dates, in addition to expiration dates inclusive of PTA, for any families of U.S. patents with similar claimed subject matter.

In litigation, such as Hatch-Waxman litigation, the Allergan decision will eliminate one potential defense for the first-filed, first-issued patent in a family. In addition, the Allergan decision will affect litigation and settlement strategy through its clarification that the longest possible patent term — setting aside PTE — for a particular patent family is set by the first-filed, first-issued patent.

It will be increasingly important to ensure that the first-filed, first-issued patent in a family has significant litigation value, to assess the need for terminal disclaimers in later family members, and — for patents related to pharmaceuticals — to ensure an informed view of the exclusivity timeline for a drug from a litigation perspective.

On Sept. 26, the generics filed a petition for rehearing and en banc review at the Federal Circuit, arguing that the panel's decision conflicts with precedent, and that the "only date that really matters [for ODP purposes] is patent expiration."[8]

[1] Allergan USA, Inc. v. MSN Laboratories Private Ltd., 111 F.4th at 1358 (2024).

[2] In re Cellect, LLC, 81 F.4th 1216 (2023).

[3] Allergan, 111 F.4th at 1364.

[4] Id. at 1368, citing Cellect, 81 F.4th at 1229.

[5] Id.

[6] Id. at 1369.

[7] Id.

[8] Petition for Panel Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc, 16-17, quoting Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd., 753 F.3d 1208, 1215-16 (Fed. Cir. 2014), internal quotations omitted.

Group Contacts

This content is provided for general informational purposes only, and your access or use of the content does not create an attorney-client relationship between you or your organization and Cooley LLP, Cooley (UK) LLP, or any other affiliated practice or entity (collectively referred to as "Cooley"). By accessing this content, you agree that the information provided does not constitute legal or other professional advice. This content is not a substitute for obtaining legal advice from a qualified attorney licensed in your jurisdiction, and you should not act or refrain from acting based on this content. This content may be changed without notice. It is not guaranteed to be complete, correct or up to date, and it may not reflect the most current legal developments. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. Do not send any confidential information to Cooley, as we do not have any duty to keep any information you provide to us confidential. When advising companies, our attorney-client relationship is with the company, not with any individual. This content may have been generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence (Al) in accordance with our Al Principles, may be considered Attorney Advertising and is subject to our legal notices.